My grandfather, John Henry, possessed a mastery of storytelling that filled the room with warmth. When the rain beat against the windowpanes, or the ice or snow kept me inside, I’d perch myself on the floor near his rocking chair, mesmerized by the tales of his youth in rural Texas, his days as a soldier in the US Army, and the harrowing battles in France. With each word, he painted vivid scenes of the struggle and resilience of his family during the tumultuous depression years in 1930s California. Pausing only to adjust his fiddle, John Henry would then draw the bow across the strings, filling the room with a lively jig that seemed to echo the resilience and spirit of those days and family members long ago passed on. When my grandfather passed, my father, as any good son would do, took the helm, recounting those years in California and beyond. A few drinks of good scotch whiskey for us both lit up his memory and released his vivid imagination. The more scotch we consumed, the more colorful his recounts, so parts of this story may be a bit grandiose.

Bringing Blind Jelly Roll Jackson and Le Petite Fromage into the string band’s musical circle infused the fellows with newfound assurance. John Henry found himself utterly taken aback by their musical prowess.

Johnny and the string band continued to improve with each passing week. After six months of playing front porch shows, birthday parties, a few illegal chicken fights, and one funeral, W6XAI Bakersfield, the most influential radio station in California, came calling. The station approached the band with an offer to perform a thirty-minute live show. Le Petite’s Daddy, Baby Boy Fromage, used his questionable connections to secure the band’s spot on the show, as his own band, The Chigger Bayou Boys, were regulars on the hillbilly program hosted by Colonel Bromide A. Seltzer. The esteemed Colonel was famous for featuring the latest talents on his popular daily show, always staying on the lookout for fresh and promising acts he could sign to a strangeling management contract that left him flush with cash and the talent with a pittance. Blind Faith fitted his bill.

Baby Boy Fromage arranged for transportation to and from Bakersfield. The radio station had agreed to pay the boys $75. 00 for the show, which included four commercials for Father Flannigan’s Holy Healing Tonic, Sister Aimee’s Blessed Miricle Face Cream, and Puffy Cloud Lard. In today’s world, that kind of money might buy you a mediocre supper at an Olive Garden, but in the Depression years, it was a small fortune. Of course, Baby Boy would require a chunk for providing the transportation and a meager finder’s fee for getting the band on the show. All said and done, Blind Faith would make $40.00 cash to split six ways. Le Petite had warned the boy that her father’s deals can sometimes border on nefarious, so don’t cry like a freshly born titty-baby if the whole thing flushes down the toilet.

Around noon on Saturday, the stagecoach to Bakersfield arrived at the Strawn residence. Le Petite’s daddy had promised luxury transportation for the haul to Bakersfield. Baby Boy’s idea of a luxury transport was a converted Tiajuna Taxi, complete with no less than a hundred bullet holes along each side of the vehicle. Two church pews nailed to the wooden floor served as seating, and the big stain on the floor was likely blood. The driver was a Mexican chap who didn’t speak English and drove with a bottle of Tequila planted in his lap. His GPS was a ratty map with the route colored in red crayon. Le Petite was furious with her daddy and planned to smack his big head with a *cajun blamofatchy.

Arriving at the station, the band was led into a large room where the broadcast would take place. A small stage covered with short nap rugs and a half dozen microphones placed where each musician would stand. Another band, The Light Crust Doughboys, from Fort Worth, Texas, was packing up, having completed their live show for their sponsor, Light Crust Flour. They were in Hollywood to be in a Western movie with Gene Autry, and this was their last commitment before heading back to Texas. Johnny spotted their fiddle player, made a bee-line over, and introduced himself. The man, Bob Wills, a fellow Texan, wanted to hear youngsters play, so he stuck around for the live show, which was due to start in twenty minutes. The radio technicians placed each member in front of a mic, giving Le Petite her own microphone for singing. The band played 16 bars of music so the man in the sound booth could adjust the volume. Bob Wills sat in a corner, smoking a cigarette and drinking what appeared to be a pint bottle of hooch hidden in a brown paper sack.

The two announcers, a heavy-set fellow wearing a black cowboy hat and his companion, a boney, skittish little gal, also wearing a matching cowgirl hat and white boots, took their positions in front of a microphone next to a nervous Le Petite. The man told the band that when that light on the wall turns from red to green, that means we are live, and you start your theme song while we announce you and our sponsors. Jelly said he couldn’t see the light, but Pancho Villa would give him the queue. The announcer asked Johnny if that man was blind? Johnny said, “Yep, blind as a bat but he’s a pretty good driver and got us here in one piece.”

The boys had no theme song, so Jelly told them to play Red River Valley: You can’t mess that one up. The man at the mic counted down, the light turned green, and the boys let loose on their new theme song. All the time, the two announcers were jabbering about their sponsors.

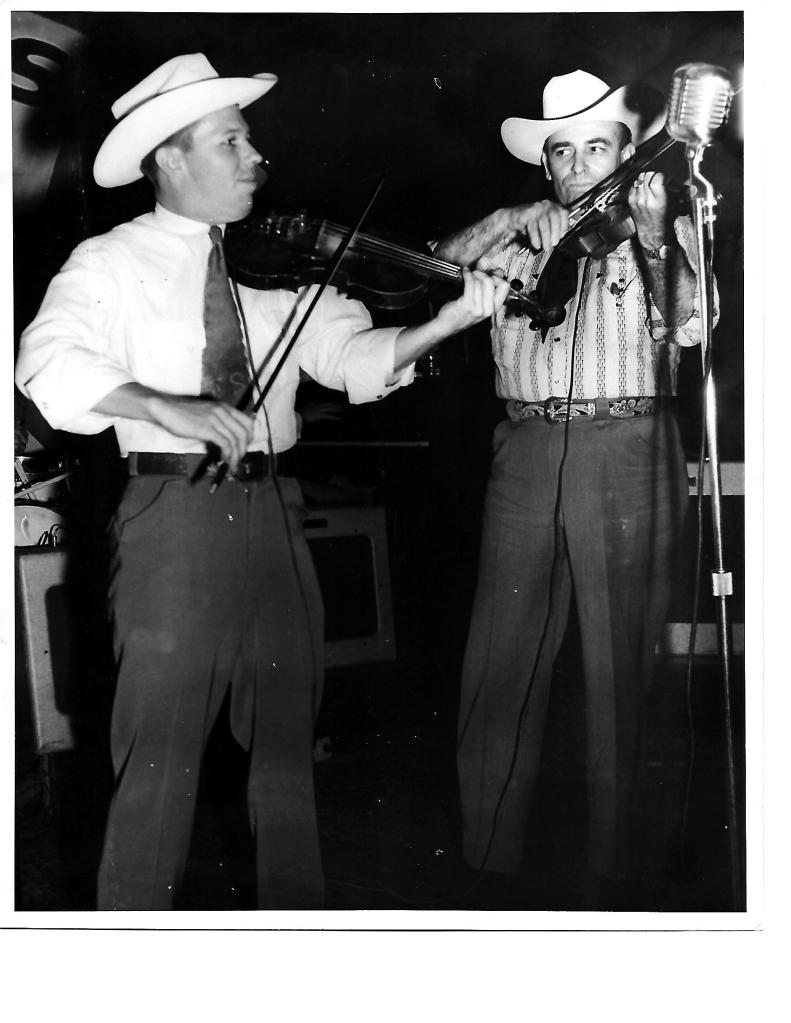

The announcers stepped back from the microphones and gave the boys a thumbs-up to start their show. Le Petite counted off a cajun song about a “Big Mamou” and went into “Will The Circle Be Unbroken” and then “Cold Beer and Calomine Lotion.” The band played every tune they knew, finishing up with Johnny playing a fiddle tune called “Lone Star Rag,” which caused Bob Wills, with a big grin on his face, to rise from his chair and clap along. When the show ended, Bob gave Johnny a few pointers, telling him he had a bright future in country music and to get in touch when and if he returned to Fort Worth. Fifteen years later, back home in Texas and playing country music for a living, Johnny got in touch with Bob Wills, who became his mentor and close friend, gifting Johnny with one of his fiddles, which he is playing in this photo. I have that fiddle as well as my grandfather’s fiddle.

My father, Johnny Strawn playing twin fiddles with Bob Wills. Forth Worth, around 1952.

- * Cajun Blamofatchy is a piece of wood use