My grandfather, John Henry, walked to his job at the furniture shop. Years ago, the same place had closed down, driven by the Depression, forcing him to move his family to California for work. Now, twelve years later, he has taken giant steps back, from a good job in Los Angeles to once more building furniture for an hour’s wage. Defeat weighs heavily in his heart. Middle age has come, and the future is murky. So, doing what men do, he keeps walking, counting his steps to nowhere. There are many to blame, but he alone bears the burden of his failures.

The iced ground crunches under his shoes. The cold goes to his bones. His jacket is no match for this weather. He favors the feel of the ground beneath his feet over the Ford sedan in the garage, which is idle most of the time and now a home for mice and other wandering critters.

After the upsetting homecoming with his father, Johnny walked a few blocks to the small neighborhood grocery store to call his best friend, Dick Hickman. His father remained firm in his decision about the telephone, vowing to never have one in the house. The old man viewed the contraption as a rattlesnake in a bag. Lousy news reached him in time enough; no reason to expedite misery.

Two sisters from Germany ran the store, always open, even when the ice storm howled outside. They preferred work to idleness; a dollar was worth more than knitting by the stove. They missed their homeland, but not the darkness that had settled under Hitler’s shadow. Johnny walked in and felt the warmth; they had known him since he was a boy. Following a few hearty hugs and cheek kisses, he was offered a mug of coffee, hot and strong with bourbon and a hint of cinnamon, a taste of what once was.

Dick and Johnny had forged a bond on the playground one morning; Dick was trapped by older boys, their intentions were dark, and Dick knew he was in for a ruckus. Johnny, a full head smaller than Dick, added his small fist for ammunition. A few busted lips and a bloody nose ended the altercation, and the boys would be bound for life by bloody noses and skint knuckles.

Dicks mother, a woman of stern Christian resolve, lived simply, her heart full of faith. Father Hickman was a ghost of a man, suddenly appearing from nowhere, then off again to somewhere. Mother Hickman, as she was called, gave what little extra money they had to Preacher J. Frank Norris, the charismatic leader of the First Baptist Church of Fort Worth.

Nice clothes were a luxury during the Depression, and most children at R. Vickery’s school wore hand-me-downs or worse. Dick wore the yellow welfare pants distributed by the Salvation Army, a sign that his folks were poor. Mother Hickman saw nice clothing as a sign of waste, except when it came to her Sunday fashions. Johnny had a pair of those detestable canvas pants but refused to wear them; the old dungarees with patches did just fine.

Both boys felt the weight of loss when the Strawn family left for the promised land. They exchanged a few postcards during the years in California. Nevertheless, they adhered to the unspoken rule that young men did not write to one another. This was a relic of manly notions of the time. A line or two every six months was enough. Both joined the Navy around the same time, meeting briefly in Pearl Harbor. Then came the seriousness of war. Young sailors, they carried on.

Dick arrived at the two sisters’ store to fetch Johnny. His transportation was a rattle-trap Cushman motor scooter. It refused to stop on the icy street. The scooter slid on its side into the curb and threw Dick off of the beast. The ride to Dick’s apartment was a jolt, far worse than the taxi. Johnny vowed to buy a car when the weather cleared, maybe one for his buddy, too. He held a tidy wad of cash from Hawaii.

A brotherly deal was struck. Johnny would share Dick’s large apartment on Galveston Street, splitting the rent and bills evenly. They were friends again, but now men, and they had different thoughts, dreams, and needs. Dick was courting a young woman from Oklahoma and doing a miserable job of it. Still, marriage lingered in the air, heavy like the rich aroma of brewing coffee, the kind they both drank too much of. Dick took his poison with cream and sugar; Johnny preferred his black and strong.

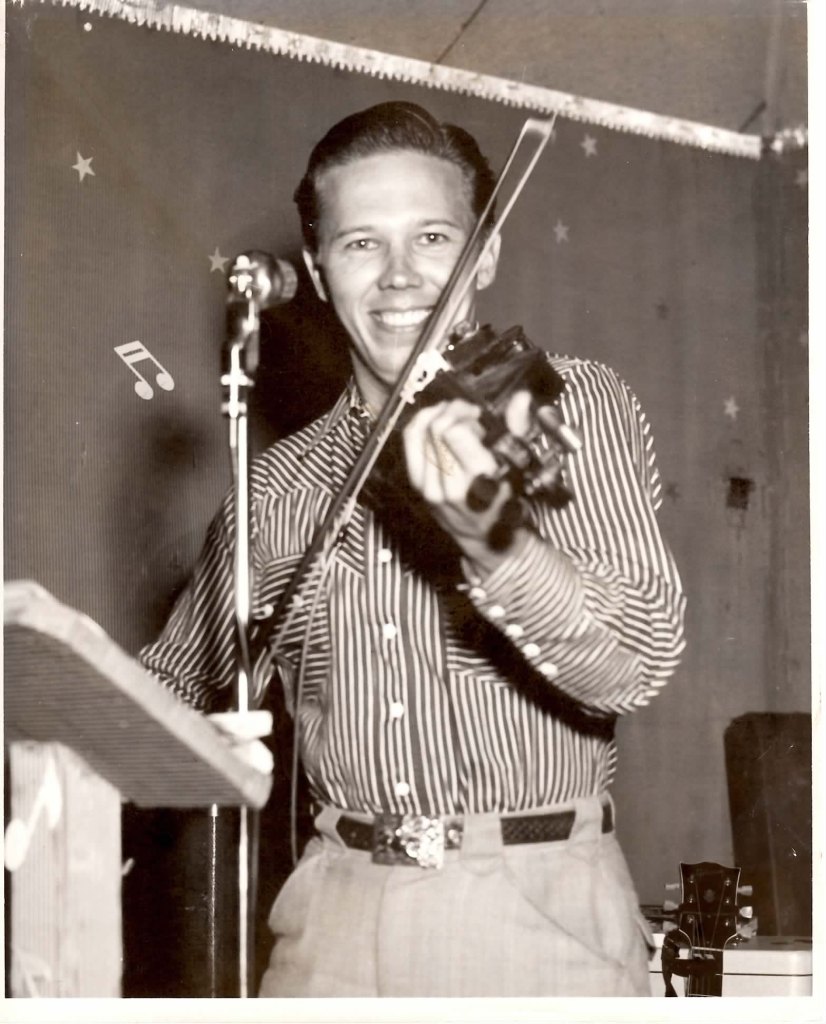

Johnny’s goal was to play music for a living, and this was the right city to make that happen. He joined the musicians’ union and sent a message to Bob Wills that he was back in Fort Worth.

Wills was now the celebrated band leader of the western swing band, The Texas Playboys. He remembered that meeting at the radio show in Bakersfield, California, long ago. The boy stood out. It was no small feat because Wills was the finest fiddle player in country music.

Bob Wills was not a man known for kindness. He could be brash and indifferent to fans and bandmates alike. Yet, for Johnny, he made an exception. Bob took the young man under his wing, becoming a mentor to my father. A few calls were made, and the boot was in the door. Johnny secured auditions at some of Fort Worth’s best clubs, and each went well. Bob invited him to rehearse with the Playboys. It was there he met men who would soon be legends in country music. A few years later, he would find himself in that circle.