After two months in Hawaii, homesickness crept in. Johnny missed his music and his string band, Blind Faith. His prized fiddle stayed behind, locked away in the hall closet. His father assured him that it would be well cared for.

Norma, his sister, wrote each week; her letters were either sharp with bitterness, primarily toward their mother, or filled with hilarity about life at home. His dog, Lady, lingered in his thoughts, her absence a weight; she is old and might not be alive when he returns.

Once again, in the clutch of her elixirs and perhaps something more potent, his mother continued her assault by missives. Johnny read a few, sensing something wrong. She sounded unsteady, lost. Her words were jagged, and he promised himself no more. He would not carry the burden of the guilt she heaped upon him. Her pen was poison.

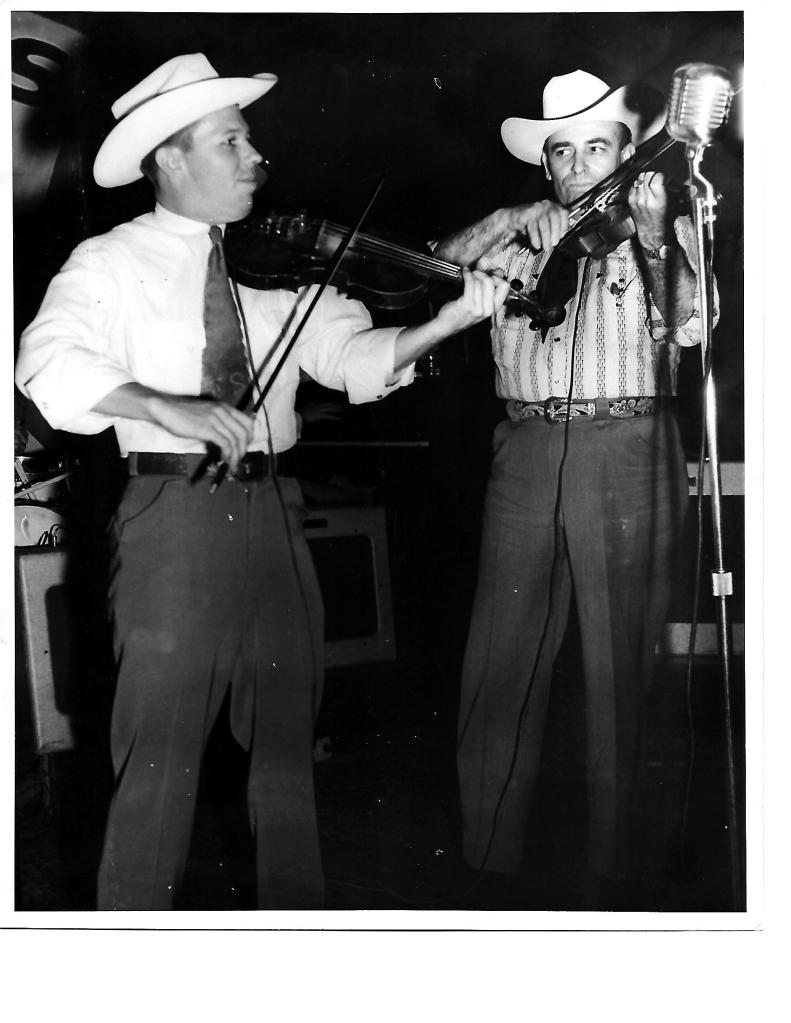

A music store sold him a fiddle for ten dollars. The owner was an old Korean man who made a few adjustments, adding new strings and setting the bridge and sound post just right. It did not sound as sweet as his own, but now he had a fiddle, giving him a spring in his step. He needed musicians. His commanding officer, walking by the barrack, heard Johnny practicing. Whenever he had spare time, he sat on a wooden crate under the shade of a Koa tree behind the barracks, entertaining the birds perched in the tree. The officer from the South Texas town of Corpus Christi offered to connect him with musicians he knew. True to his word, two sailors came to Johnny’s Quonset Hut the next day. One was a guitar player named Jerry Elliot, a fellow Texan, and the other was Buzz Burnam, who played the doghouse bass fiddle. Buzz, a Western Swing musician from Albuquerque, knew a few other musicians who might be interested in jamming. They set a practice day and time to meet under the Koa tree. Johnny’s homesickness eased a bit.

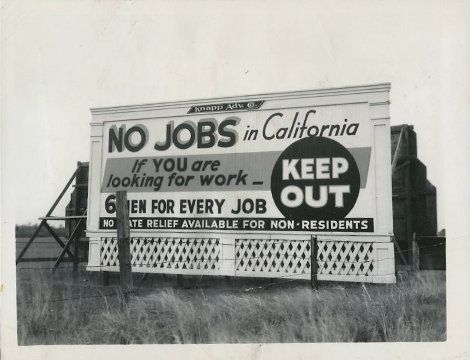

A letter from Le’Petite Fromage gave Johnny another lift. She and her husband, Montrose, the trumpet player from Sister Aimee’s orchestra, had a baby child named Savon, an old Cajun family name. They planned to stay in Chigger Bayou, and she would sing in her father’s band if and when he returned from California. Her mother, Big Mamu, said life was better without him underfoot. She had told Johnny many times that girls in the Bayou are expected to be married with a child on each hip by the age of eighteen. Tradition got the best of her. Blind Faith was finished. It was a good run while it lasted.

Sunday was a day for rest, even amid the chaos of war. The sailors moved through the day with light duty on the Sabbath, their shoulders eased, and their spirits lifted after a good dose of religion found in the island’s many churches. After lunch, the two musicians arrived, bringing two more as promised, one bearing a saxophone, the other a snare drum with one cymbal. They played, and the music flowed—Western swing, big band, island tunes. It went on for hours. They were asked to play at the Officers Club in the Royal Hawaiian Hotel a few days later. The pay was meager, but they were musicians, and they knew the worth of their work was in the joy it brought, not the currency it earned.

A letter came from Sister Aimee McPherson. It told Johnny about Blind Jelly Roll. He had been hit by a car. The new seeing-eye dog, following barking directions from the blind Pancho Villa, led them across a busy street. They walked straight into the path of a vehicle. Everyone survived, but Blind Jelly Roll broke his left arm. His hand was crushed under the tires. It seemed unlikely he would ever play the blues again. She would keep him on as the music director and spiritual advisor. She loved that old black man and his ill-tempered Chihuahua deeply.

Sometimes, good luck strikes like lightning hitting the same ground. Johnny felt it. His C.O. asked him to help with the weekly base paper. This led him to work at the Pearl City News when off duty. He became the leading writer. Two sailors he knew were on staff, too. The pay was little, but he saved every cent until he had a decent stack of bills. He rented a lot in downtown. Then, he bought two used cars from an officer. They sat there for sale. The drugstore next door took names for those who inquired, and Johnny made appointments to sell. Two cars turned to three, then five, then ten. Two young Hawaiian boys washed them twice a week. Johnny sat beneath a small canopy that served as his office. He sold cars, saved money, bought more, and eventually acquired the lot and four more on that block. In a year, he owned a few small buildings and all remaining vacant lots—almost an entire city block in east downtown Honolulu. After his Navy discharge, he rented a room in a house owned by the old Korean man who owned the music store. He was taken aback when he met the man’s young granddaughter, who was his age. They both sported arrows in their backs, shot by the mythical fairy, Cupid. Returning to Los Angeles was now out of the question.