Junior Gives Fort Worth The Blues

An old friend of mine passed a few months ago. We had been apart for years, yet he held a distinct place in my thoughts. I sometimes borrowed fragments of his vivid life for my short stories, which pleased him. His name was simply Junior. He believed a last name was of no consequence and cared little for family ties.

In 1957, he opened a coffee house in the heart of downtown Fort Worth, Texas. Although they will tell you that “The Cellar” was the first, the “Hip Hereford” came first by a full year.

Junior was born to be a cowboy. His father, grandfather, great-grandfather, and all the uncles and cousins wore the same boots and lived by the code of the West. There were more cowboys in his bloodline than in a John Wayne film. It should have been his fate. But then, his favorite horse, Little Bill, kicked him hard in the head. After that, he turned his back on the rugged ideals of the West. He became the owner of a coffee house club, a renaissance man, a poet, and a man who lived life like a Stetson-wearing beatnik. He said a life spent on a sweaty saddle, inhaling the stench of cattle farts, was not the life he dreamed of.

The opening night for the coffee house was Halloween 1957. Junior hires two street winos to help run the door and do odd jobs. They were reluctant to give him their birth names, so he christened them Wino 1 and Wino 2. They were good to go as long as Junior paid them and kept the booze flowing. The following is an excerpt from the unfinished story.

Around 7:15, Wino 2 informs Junior that the first performer has arrived and takes the stage for the introduction. He steps to the mic and, in that pleasant voice, says, “Ladies and gents, please welcome to the stage, Mr. Blind Jelly-roll Jackson and his nurse Carpathia.”

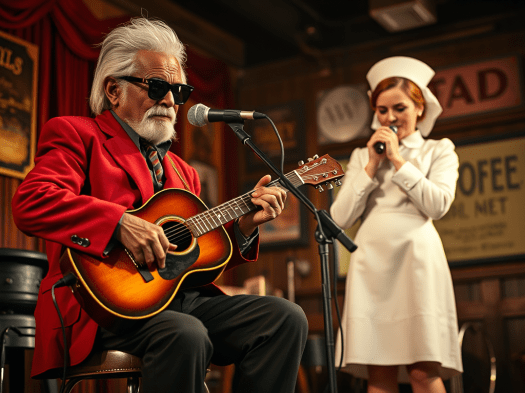

An ancient black man with hair as white as South Texas cotton, holding a guitar as old as himself, is helped to the stage by a prim female nurse dressed in a starched white uniform. The old man wears a red smoking jacket, a silver ascot, and black trousers. Dark sunglasses and a white cane complete his ensemble. The old fellow is as blind as Ray Charles.

The nurse gently seats the old gentleman in a chair provided by Wino 1 and lowers the large silver microphone to a height between his face and his guitar. She then stands to the side of the stage, just out of the spotlight. Blind Jelly Roll starts strumming his guitar like he’s hammering a ten-penny nail. Thick, viscous down strokes with note-bending riffs in between. His frail body rocks with every note he coaxes out of his tortured instrument. He leans into the mic and sings,

“We’s gonna have us a mess o’ greens tonight…haw..haw..haw…haw…gonna wash her down with some cold Schlitz beer..haw..haw..haw..gonna visit ma woman out on Jacksboro way…gonna get my hambone greased”. This was Texas blues at its best.

On cue, his nurse steps into the spotlight, extracts a shiny Marine Band harmonica from her pocket, and cuts loose on a sixteen-bar mouth-harp romp. Her ruby-red lips attack that “hornica” like a ten-year-old eating a Fat Stock Show Corndog. The crowd loves it. They dig it. When Blind Jelly Roll finishes his song, Wino 2 passes a small basket through the group for tips. Jelly Roll and his nurse take their kitty and depart. He’s due back at the old folk’s home before midnight.