“Do not forsake me, oh my Darlin,” on this our wedding day,” who didn’t know the first verse of that song from the radio? A massive hit from the 1952 movie “High Noon,” performed by everybody’s favorite singing cowboy, Tex Ritter.

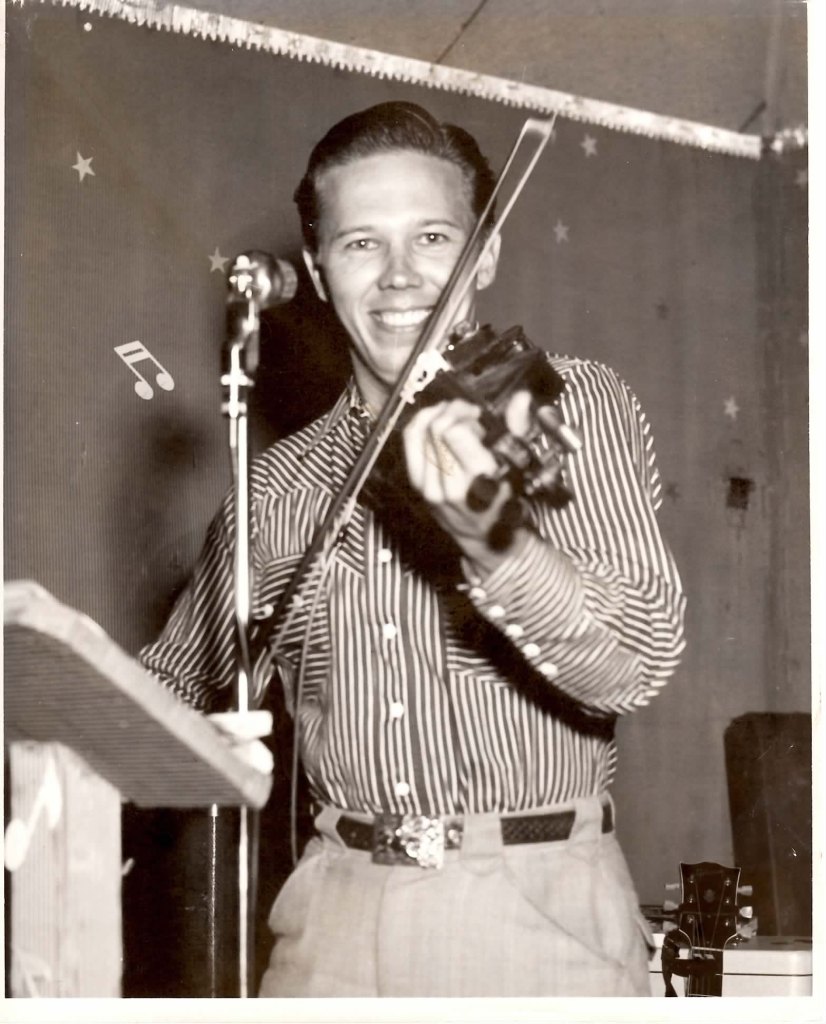

In 1957, I was eight years old, and on some Saturday nights, I got to tag along with my father to the “Cowtown Hoedown,” a popular live country music show performed at the Majestic Theater in downtown Fort Worth, Texas. My father was the fiddle player in the house stage band, so I was somewhat musical royalty, at least for a kid.

Most of the major and minor country stars played Fort Worth and Dallas as much as they did Nashville, and I was fortunate to have seen many of them at this show. One, in particular, made a lasting impression on my young self.

I was sitting on a stool backstage before the show, talking to a few kids; who, like me, got to attend the show with their fathers.

My father came over and asked me to follow him. We walked behind the back curtain and stopped at a stage-level dressing room. There in the doorway stood a big fellow in a sequined cowboy suit and a 30 gallon Stetson. I knew who he was; that is Tex Ritter, the movie star and cowboy singer. My father introduced me, and I shook hands with Tex. I was floored, shocked, and couldn’t speak for a few minutes. What kid gets to meet a singing cowboy movie star in Fort Worth, Texas? I guess that would be me.

Tex asked my name and then told me he had a son the same age as me. We talked baseball and cowboy movies for a bit, then he handed me a one-dollar bill and asked if I would go to the concession stand and buy him a package of Juicy Fruit chewing gum. So I took the buck and took off down the service hallway to the front of the theater. I knew all the shortcuts and hidey holes from my vast exploration of the old theater during the shows.

I knew nothing of the brands and flavors, not being a gum chewer, but the words Juicy Fruit made my mouth water. Not having much money, what change I did get from selling pop bottles went to Bubble Gum Baseball Cards, not fancy chewing gums.

I purchased the pack of gum for five cents. Then, gripping the change tightly in my sweating little hand, I skedaddled back to Tex’s dressing room. He was signing autographs but stopped and thanked me for the favor. He then gave me two quarters for my services and disappeared into his dressing room for a moment. He handed me an autographed 8×10 photograph of him playing the guitar and singing to the doggies when he returned. I was in country and western music heaven. He also gave me a piece of Juicy Fruit, which I popped into my mouth and began chewing, just like Tex.

Juicy Fruit became my favorite gum, and now, whenever I see a pack or smell that distinct aroma as someone is unwrapping a piece, I remember the night I shared a chew with Tex Ritter.