I’ve recently sprouted a beard, and much to my surprise, not a single dark hair dares to intrude upon my snowy facial wilderness: the scruffy testament to my frothy mirth matches the proud hue atop my head, a delicate white crown. As a son of Cherokee lineage, I stood astonished, finding myself transforming into an old man with pearly locks in my forties. This change, I suspect, is the handiwork of my father’s Scotch-Irish heritage—a rowdy clan of kilted revelers who seemed to navigate life with laughter and a touch of mischief. They must have commandeered a ship, setting sail for New York, then onto Pennsylvania, where the merry-making reached promising heights. My grandfather would neither confirm nor deny the wild tales of our kin. This speaks volumes about my love for Irish Whiskey, while the Cherokee blood in my veins draws me to large, sharp knives. Hand a drink to an Indian, and trouble isn’t far behind. History whispers of how Little Bighorn ended for Custer. Loose chatter suggests that Sitting Bull and Howling Wolf snagged a wagon load of drink the night before the fray, bestowing upon the braves a reckless spirit. Had they chosen an early night with a hearty breakfast of Buffalo tacos, perhaps the bloody disaster would have been averted.

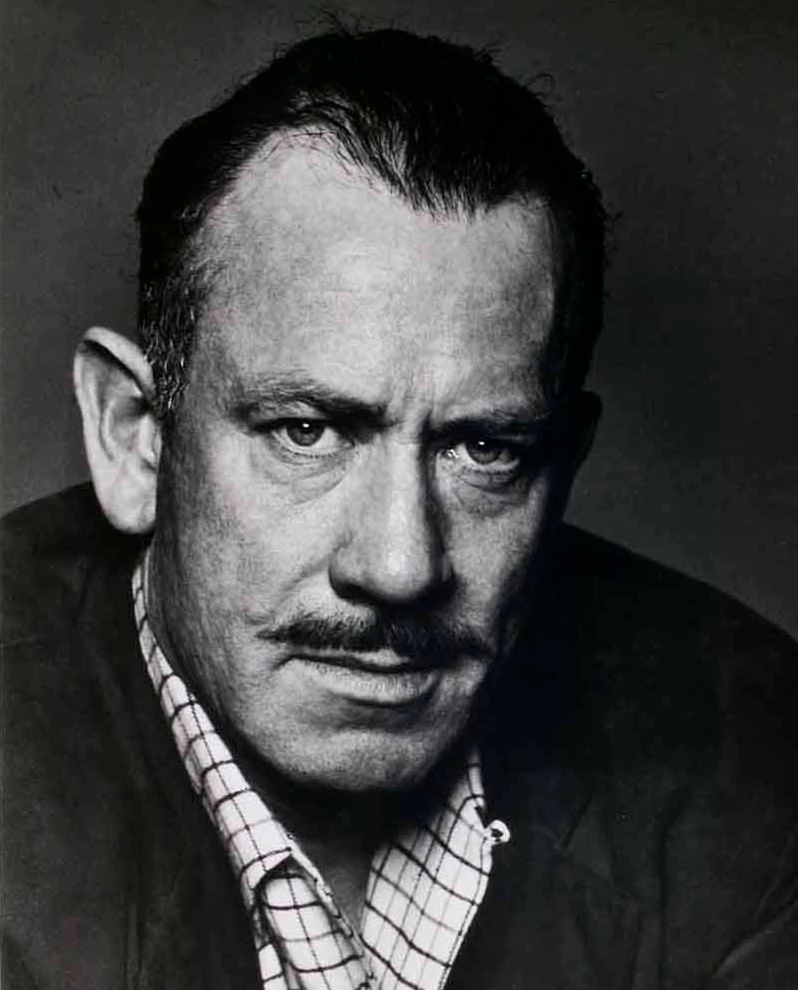

As a boy of nine, I dreamt of writing like Twain. In my innocence, I thought I was his spirit reborn, dropped into a different time: September of 1949, the last year of the baby boomer generation. With a Big Chief Tablet and a number 2 pencil, I set out to capture the simple chaos of childhood mischief. There were four of us, bold and reckless, stealing cigarettes, hurling water balloons at police cars, and fighting with the tough kids across the tracks. The local papers laughed at my tales as if a child’s imagination could not hold weight. My aunt, wise and educated, introduced me to Spillane and Steinbeck. Spillane turned me into a wise-ass, insufferable child, resulting in numerous mouth cleansings with Lifeboy soap. Steinbeck felt right—my family had lived a life like Tom Joad’s, migrating to California during hard times of the Dust Bowl and the 1930s. I had stories in me, maybe even a book. A therapist dismissed it as a childish fantasy, saying it would fade. Yet here I am, much older, still tethered to that innocence. Now, I’m in my Hemingway phase, my looks echoing the rugged man who lived wild in Cuba, writing furiously while embracing the chaos of life.

There is more sand in the bottom of my hourglass than in the top. I feel the end approaching. I do not wish to know the day or hour. I can only pray it is a good one, resulting in a trip to Heaven, which is better than the alternative. I am not the writer Twain, Steinbeck, or Hemingway was. They had talent, and they had time from youth to hone their craft and find their voices. Yet, I will still give it a try.