The makeshift sunblock my father had fashioned from a tarp and four cane fishing poles wasn’t beautiful, but it worked fine. Sitting under the contraption was my little sister, mother, and grandmother. I was eight years old. He and my grandfather were not far away, holding their fishing rods after casting into the rough surf. Whatever they caught would be our supper that evening. I wasn’t invited to fish with them; I was too young, and the surf too dangerous. Besides, my small Zebco rod was only strong enough to catch a passing perch.

The visit was our annual summer fishing trip to Port Aransas, Texas, a small fishing village on the northern tip of Mustang Island. I don’t remember my first visit, but my mother said I was barely one year old. After that, the Gulf of Mexico, the beach, and that island became part of my DNA

I’m an old man now, but I can recall every street, building, and sand dune of that small village. Over the decades, it became a tourist mecca for the wealthy, destroying the innocent and unpretentious charm of the town. Gone are the clapboard rental cottages with crushed seashell paving and fish-cleaning shacks. Instead, rows of stores selling tee shirts made in China sit between the ostentatious condominiums, restaurants, and hotels. I prefer to remember it as it was in the 1950s when families came to fish, and the children explored the untamed beaches and sand dunes.

Born in 1891, my grandfather was an old man by the time I was eight years old. Tall and lanky, with white hair and skin like saddle leather. He was a proud veteran of World War 1 and as tough as the longhorn steers he herded as a boy. He lost part of his left butt cheek from shrapnel and was gassed twice while fighting in France. Nevertheless, he harbored no ill feelings toward the Germans, even though he killed and wounded many of them.

On the contrary, he disliked the French because they refused to show proper gratitude for the doughboys saving their butts from the Krauts. As a result, he wouldn’t allow French wine in his home. He preferred Kentucky bourbon with a splash of branch water or an ice-cold Pearl beer. He left his hard-drinking days in Fort Worth’s Hell’s Half Acre decades ago. He told a few stories about the infamous place, but he was careful to scrub them clean for us youngsters.

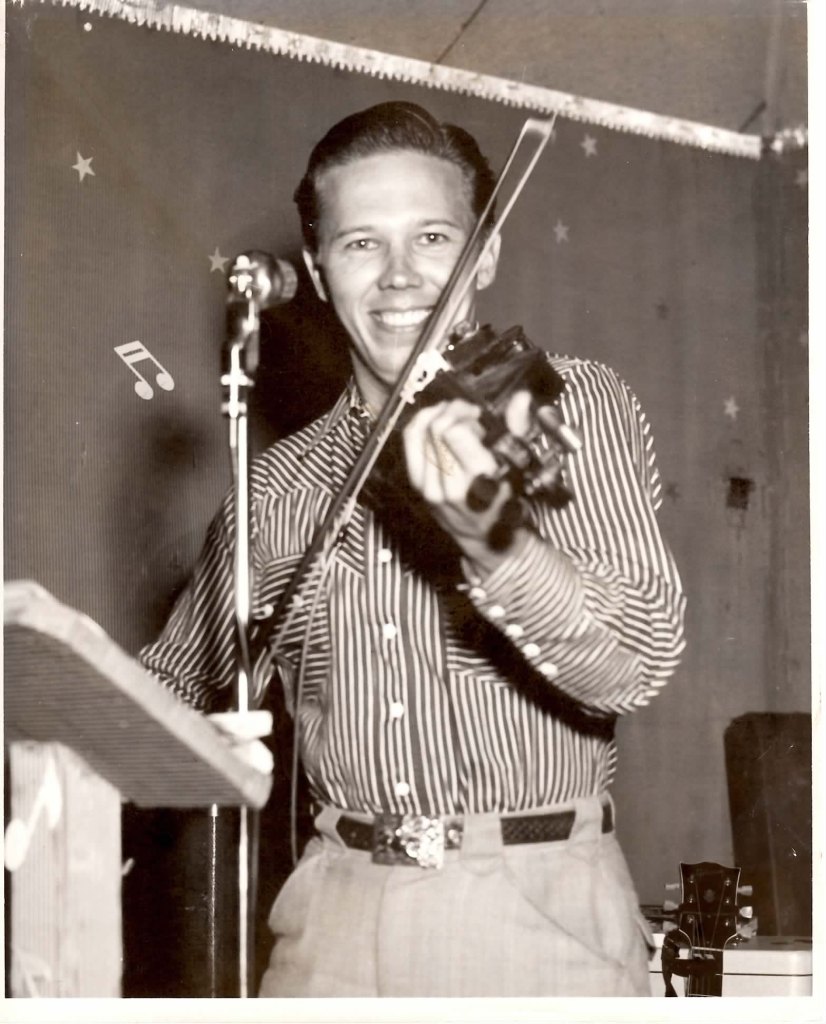

His one great joy in life was saltwater fishing with my father, playing his fiddle, and telling stories to whoever would listen. The recounting of his early childhood and life in Texas captivated my sister, cousins, and me for as long as the old man could keep talking. He told about being in France but never about the horrors of the war. He lived a colorful childhood and, for a while, was a true Texas cowboy. Half of it may have been ripping yarns, but he could tell some good ones. My mother said I inherited his talent for recounting and spinning yarns. If that’s true, I’m proud to have it.

He could have been in a Norman Rockwell painting while standing in the surf, a white t-shirt, a duck-billed cap, and khaki pants rolled to his knees. I was in awe of the old man, but I was too young to know how to tell him. My grandmother said he was crazy for wearing his gold watch while fishing.

The timepiece was a gift of gratitude from his employer when he worked in California during the Depression years. A simple gold-plated 1930s-style Bulova. It was an inexpensive watch, but he treated it like the king’s crown, having it cleaned yearly and the crystal replaced if scratched. He called that watch his good luck charm and wore it when fishing for good juju. It was a risk that the salt water might ruin it, but he took it. He caught five speckled sand trout and half a dozen Golden Croaker that day, so the charm worked. Add the three specs my father snagged, joined with the cornbread and pinto beans my mother and grandmother cooked, and we dined like the Rockefeller’s that night.

The next few days were a repeat of the same thing. I rode my blow-up air mattress in the shore break and caught myself a whopper of a sunburn on my back. The jellyfish sting added to my discomfort. I was miserable and well-toasted, but I kept going, determined to enjoy every second of beach time.

We returned to Fort Worth as a spent and happy bunch. The family would give it another go the following year.

Two years passed. One day, my father told me my grandfather was sick and would be in the veteran hospital in Dallas for a while. He mentioned cancer. I was young and didn’t understand this disease, so I looked it up in our encyclopedia and then understood its seriousness. One week, he seemed fine, sitting in his rocking chair playing his fiddle and telling stories, and the next week, he was in a hospital fighting for his life. His doctor said being gassed in the war was the cause of his cancer. It was not treatable and would be fatal.

Near a month later, he was not the same man when he came home. His face was gaunt; his body, which was always lean and wiry, was now skin and bone. The treatments the doctors ordered had ravaged him as much as the disease. My grandmother’s facial expressions told it all. There was no need to explain; I knew he would soon be gone. My father was stoic, if only for his mother’s benefit. His father, my grandfather, was fading away before our eyes, and we couldn’t do a thing to change the outcome.

A week after returning home, Grandfather found his strength, walked to their living room, and sat in his rocking chair. He asked me for his fiddle, which I fetched. He played half of one tune and handed it back to me. I cased it and returned it to the bedroom closet; he was too weak for a second tune. His voice was raspy and weak when he spoke, but he had something to say, so I took my position on my low stool, as I often did when he recounted his tales. I noticed his gold watch was loose and had moved close to his elbow. His attachment to the timepiece would not allow removal. It was a part of him. He spoke a few words, but continuing was a painful effort. My grandmother helped him to his bed. He removed his watch, placed it on the nightstand, and lay down. He was asleep within minutes. From that day on, he would sleep most of the time, waking only to be helped to the bathroom or to sip a few spoonfuls of hot soup. I would visit after school, sitting next to him while he slept, cleaning his watch with a soft cloth, winding it, and ensuring the time was correct. I felt he knew I was caring for this treasured talisman.

I came home from school on a Friday, and my grandfather was gone. I could see the imprint in the bed where he had laid, and his medication bottles and watch were missing from the nightstand. Mother said he took a turn for the worse, and my father took him back to the veteran’s hospital.

The following day, my father came home and told us my grandfather had passed away during the night. I noticed he was wearing his gold watch. I thought if the timepiece was such a lucky charm, as I had been told all these years, why had it not saved my grandfather?

Life continued on Jennings Street; for me, some of it was good, and a little of it was not. Father wore grandfather’s watch in remembrance and respect. He waited for the magic to come. He gave me his worn-out Timex, which was too big for my wrist, but I wore it proudly.

The magic of the watch began to work for my father. He acquired two four-unit apartment houses near downtown, fixed them up a bit, rented them out, and sold them. We then moved to Wichita Falls, where he started building new homes. A year later, we moved to Plano, Texas, where he continued to build houses. It appeared the good luck of the watch was working overtime. I became a believer in this talisman. The hard days in Fort Worth were well behind us now. The future held promise for our family.

On a day in 1968, riding with my father to lock his homes for the night, we had a long overdue father-to-son talk. I rarely saw him because of his work, so I welcomed the time. Had I thought about college? What was going on in my life? I played in a popular rock band, so that was a point we touched on. He didn’t want me to become a professional musician as he had been. I assured him this phase would end soon. He and my mother were worried I would be drafted and sent to Vietnam. We talked for two hours. He remarked that as long as he wore his father’s watch, everything he touched turned gold. My father was successful, so how could I doubt his beliefs?

In the summer of 1969, the band on the old watch broke while we were fishing for Kingfish in the gulf off Port Aransas. While gaffing a Kingfish, my father bumped his wrist against the side of our boat. The watch fell into the water, and in a flash, it was gone. He said that if he had to lose it, this was a fitting end, lost to the water his father loved so much.