It was quite a weekend for us average Americans. A former and possibly future president was almost assassinated by a twenty-year-old anti-social nut-job, the recipient of school bullying. Take note of anyone who was ever bullied, pushed, or spoken to in a demeaning manner in your high school days. Shooting people is not the panacea.

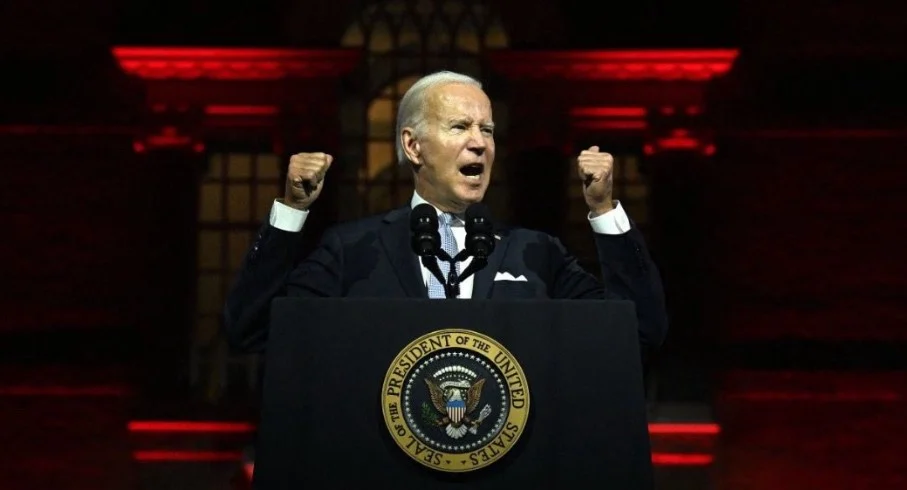

The present commander-in-chief hesitated for two hours before delivering a statement. When it finally came, it was a brief, confused jumble, possibly crafted by (not a medical professional) Jill Biden. It urged for a reduction in the aggressive language and insinuated that this was the result of America’s conservative faction. Now that’s damn sure taking it down a notch or two, Mr. President..keep it up.

You know those individuals on the right side? They are the regular, hardworking, blue-collar folks driving the pickup trucks they use in their trade. They build our homes and buildings, repair our plumbing and electrical, check out our purchases at the grocery store, pave our roads, support their kid’s little league and soccer teams, and tithe what they can to their church. These folks are struggling to afford basic necessities under Biden’s economic H-bomb. I highly doubt they have time for violence. Just getting by consumes all their energy and money. The welder with a family of five now has to saddle the debt of some woke child’s college loan for a worthless degree in Social Media Posting or perhaps Taylor Swift Music Theory. The parents want the dependent swindler out of their home; they require the kid’s room for their podcast studio. And let us not forget the ten million illegals that have invaded our country; they are living in luxury hotels and receiving hefty benefits for being criminals. All the Democrats ask is that they vote for their candidate when they are allowed to cast a ballot. Ask the homeless mother with a few children, living in a cramped shelter, or perhaps on the streets or in her minivan how she feels about the invasion of foreign grifters draining our social services when she can’t get a damn dime, a meal, or a room at Motel 6.

I’m an old fella turning 75 come September, and I ain’t liking it at all. Every joint aches, and the fear of major organs giving out is as real as can be. Momo, my missus, is a few years behind me and is dealing with many of the same issues.

We both grew up in the 1950s and were teenagers in the 1960s. I remember I was in seventh grade when Kennedy got shot in Dallas. The teacher wheeled in a portable black and white Zenith TV, and the class watched those news fellas with their sleeves rolled up, cradling a black dial phone to their ear, a cigarette in each hand, and a stiff drink of bourbon just out of camera sight, doin’ their job. They broke the news to the world that our president, John Kennedy, was deceased from a shot to the head. Our little 1950s happy-happy world was shattered. The innocence was gone in a blink, and Dallas, Texas, would always be known as the city that killed Kennedy.

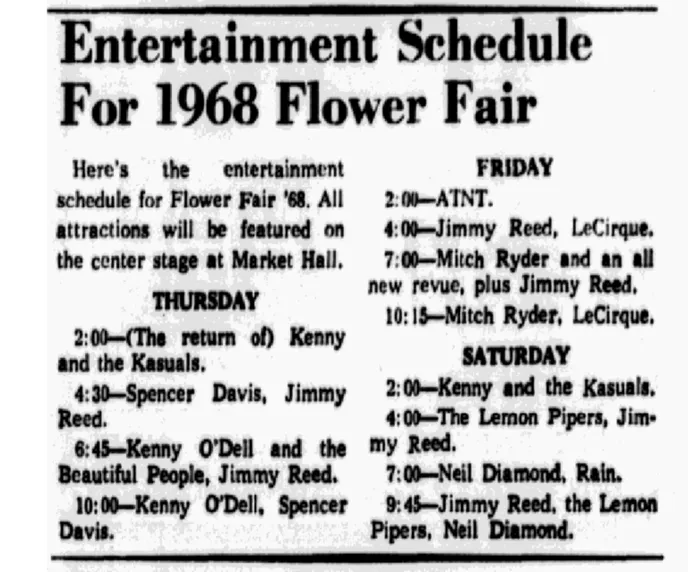

In 1968, as a high school junior, I discovered the power of the written word might actually be used to facilitate change. This era sparked within each of us the belief that we could possess the strength to change the world. We all felt we had something significant to say. During this period, I began to approach my writing with a newfound sense of earnestness. I channeled my thoughts and ideas into not only opinions for my school newspaper but also into the creation of short stories, a pursuit that became my primary focus. I would never be a Steinbeck or Twain, but I could give it one hell of a try.

When Nixon ascended to power, politics ensnared my attention. Lyndon Johnson and his Great Society pipe dream left the country in turmoil, bitterly split by his failed policies and the Vietnam War. It’s no coincidence that Joe Biden idolized Johnson and patterned himself after the arrogant bully from Texas. The familial supper table transformed into a platform for deliberating the condition of our nation. My folks remained unwavering Roosevelt democrats while I vacillated like a reed in the wind, embracing liberalism one day and conservatism the next. My loyalty belonged to no single ideology. Politicians appeared nefarious and tainted; the entirety of the government left a bitter taste in my mouth. I was not a Hippie or a Yippie, or a Yuppie, or a Guppie. Then Martin Luther King was assassinated. The good work he had done vanished within hours of his death. The lines between black and white grew wider, and violence was in the wind.

Shortly thereafter, Bobby Kennedy, the Democratic candidate for the presidency, met his tragic end in the kitchen of the hotel mere minutes after delivering a triumphant speech. The perpetrator of this heinous act, an Arab kitchen worker wielding a 22-caliber pistol, answered to the name of Sirhan Sirhan.

The Black Lives Matter movement, Antifa, and the Palestinian protest movement are powerful forces of tension in today’s society. Their intemperate assaults on our cities and citizens are vividly portrayed on our 4K television screens. Yet, when measured against the tumultuous events of the sixties, these groups appear to be more petulant young college students than Marxist terrorists.

During that era, we witnessed the emergence of formidable terrorist entities like the Symbionese Liberation Army, The Weathermen (the Weather Underground), The Students For Democratic Society (SDS), The Black Panthers, and the Ku Klux Klan, in addition to numerous other fringe groups originating on college campuses across the nation. Tossing Molotov Cocktails didn’t require a degree. These folks bombed buildings and wielded guns against Police and citizens. Patty Hearst, once the beautiful and cherished debutant darling of the Hearst publishing empire, underwent a remarkable transformation following her abduction, attributing her radical shift to the influence of the SLA’s brainwashing techniques. No, Patty, you got off on the whole terrorist ideology. Today, she is a wealthy matron with more money than she could ever spend. It leaves me pondering whether she still possesses that automatic rifle and beret from her revolutionary days.

The upcoming Democratic Convention is scheduled to be held in Chicago, reminiscent of its 1968 counterpart. During that time, a multitude of protesters, guided by the aforementioned organizations, flocked to the city, turning its streets into a battleground as they engaged in confrontations with Mayor Daley’s police, igniting buildings and police cars. The majority of the demonstrators aligned themselves with the Democratic party, displaying discord within their own ranks. It seems that this forthcoming convention is on track to mirror the tumultuous events of 1968.