Marfa, Texas, is one leg of the infamous Texas Triangle. Alpine, Fort Davis, and Marfa make up the redneck Bermuda Triangle and all the oddities that spring from its lands.

Momo and I have visited the quirky town a few times and plan another trip, perhaps in December. On our last trip, sitting in Planet Marfa, sipping a Lone Star beer and listening to the locals spin yarns and tall tales about the goings-on around the Chihuahuan Desert. We learned of nuclear-crazed killer Chihuahua dogs, strange lights in the mountains, the ghosts of James Dean and Liz Taylor at the Piasano Hotel, and enchanted horned toads that grant wishes. The young’uns that have relocated from Austin only add to the weirdness of the place.

The one story that folks were reluctant to rattle about was the young girl who vanished from her family’s desert home in 1965. She strolled into the desert behind their home to collect grasshoppers and other insects for a science project and never returned, and not a smidgen of evidence was ever found. A few days later, the parents noticed her prized acoustic guitar was missing from her bedroom, and their pet Longhorn steer, Little Bill, was missing from his stall. The girl often led him out into the desert to graze on the clumps of tasty grasses and plants. Lawman worked to solve the case for two decades, but no leads or culprits were found. Word around town was that space aliens had abducted her and the steer for scientific purposes or worse. No one thought much about the theory since Marfa loved that nonsense.

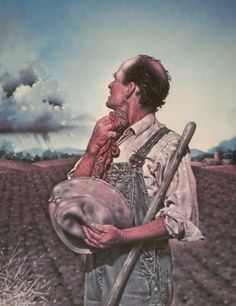

Sagebrush Sonny Toluse, the Grand Pooh-Bah of all things Marfa, tells the best version of the story. He said to a group around the bar,

“ I was walking my old doggy for his nighttime constitution. I live just outside of town, nearly in the desert, and that’s how I like it. The moon was full, so Rufus and I walked a little farther than usual. I hear guitar music from somewhere. It’s not a loud electric guitar but a soft one, like a Mexican guitar. It’s getting closer, and now I hear singing, the floating voice of a young girl. I stop, turn around, and passing by me; no more than ten feet is this little girl riding a Longhorn steer, playing the guitar, and singing an odd song I didn’t know, something about a Kay Serra or something like that. Behind her, sitting on the steer, is a giant grasshopper about half the size of the girl. I know we have big bugs here in Texas, but this critter was massive, about the size of old Rufus, my dog. The trio rode past me into the fading desert, never paying any attention to us. I was troubled by the encounter, so I went and asked the older sister, who is now an old woman, about the young girl who vanished so long ago. I told her about the ghostly encounter in the desert. She said her sister often rode the Longhorn steer like a horse and would play her favorite tune while sitting atop the beast. It was a Doris Day song, and she sang a bit. “Que Sera Sera, whatever will be, the future’s not ours to see, Que Sera Sera. “